Contemporary culture is entrenched in a cult of productivity. In fields ranging from finance to the so called “creative industries”, the value of work is increasingly measured by quantifiable outputs: logged time, completed deliverables and performance metrics assessed by data.

The dominance of digital platforms has only intensified this trajectory, giving rise to an economy where even thought processes are streamlined, time-boxed and subjected to continuous surveillance. This obsession with measurement and output leaves little to no room for ambiguity, slowness or states of mind that defy direct quantification.

In this context, intuition is often cast aside as a relic of pre-scientific thinking - vague, unreliable and unfit for serious professional work. The modern workplace, whether in tech, science, or design, favors the methodical over the instinctive. Creativity must be justified through rational processes and decision-making is validated through analytics, projections, and hard data. Intuition, by contrast, is framed as impulsive, emotional and ultimately flawed. Nevertheless, this framing ignores the nuanced, layered nature of intuition - its roots in experience, embodiment and cognition beyond language.

The Obsession with Rationalism

Architecture offices, despite their creative nature, are not immune to this culture of quantification. Deadlines, budgets and client demands have codified a workflow that mirrors corporate rationalism. Efficiency is privileged over exploration; reproducibility over resonance. Software, optimization tools and parametric models govern design processes, leading to the illusion that buildings can be solved like equations.

Yet architecture, perhaps more than any other discipline, calls for a poetics of thought, one that begins with sensation. The process of making architecture requires the capacity to feel space before it is measurable or rationalized; to know a place before it is planned. Rationalism has undoubtedly brought rigor and discipline to the field but it has simultaneously narrowed architecture’s epistemological range. Intuitive cognition - bodily, imaginal and fluid - has been cast aside and marginalized, rendered secondary to calculative thinking.

This emphasis on logic and systems reflects a Cartesian worldview, one that views the mind as separable from the body and reason as sovereign over feeling. Within this model, architecture has become an exercise in optimization rather than in transformation. The space for surprise, ambiguity and emergence - qualities fundamental to lived experience - is effectively designed out.

Intuition as Precedent to Reason

What if intuition is not the counterpoint to reason, but its precedent? Rather than opposing analytical processes, intuition may operate as a primordial mode of understanding - a subconscious connection to spatial and material possibilities that precedes intellectual abstraction. Architecture, in this frame, does not begin with analysis but with a felt resonance between body, material and place.

This idea can be traced back to Greek philosophy. In Plato’s Republic, intuition appears under the guise of noesis, a higher form of knowing that transcends both sensory input and discursive reasoning. Through his theory of anamnesis, Plato suggests that true knowledge is not acquired but recollected, intuitively recognized as if remembered. Although Plato ultimately elevated rational forms, the seeds of intuitive epistemology are embedded in his metaphysics.¹

And precisely at a metaphysical level, intuition can be understood as a cognitive function - one that perceives, processes and synthesizes information beyond the immediate and the observable. Unlike logic, which parses data sequentially, intuition operates holistically. It sees patterns, anticipates relationships, and connects seemingly scattered and unrelated phenomena. It draws upon subconscious networks of memory, embodiment and affect, assembling wholes that elude the analytical mind.

Far from being purely instinctive, intuition is heavily grounded in experience. It is the mind’s capacity to perceive the gestalt - the whole that cannot be reduced to its parts. Where logic is concerned with what is provable, intuition engages what is recognizable; what feels coherent, even if it cannot yet be articulated. It’s a kind of knowledge that is sensed before it is known, that precedes the rational categorization that often follows.

Phenomenology and the Lived Experience of Design

Modern philosophy, particularly phenomenology, brings clarity to this role of intuition. Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty reposition intuition not as irrational but as pre-rational: a perception rooted in the body, in lived experience. For Merleau-Ponty, consciousness is not detached from the world but entangled in it. The body is not merely an object among others but the very site of perception. ² ³

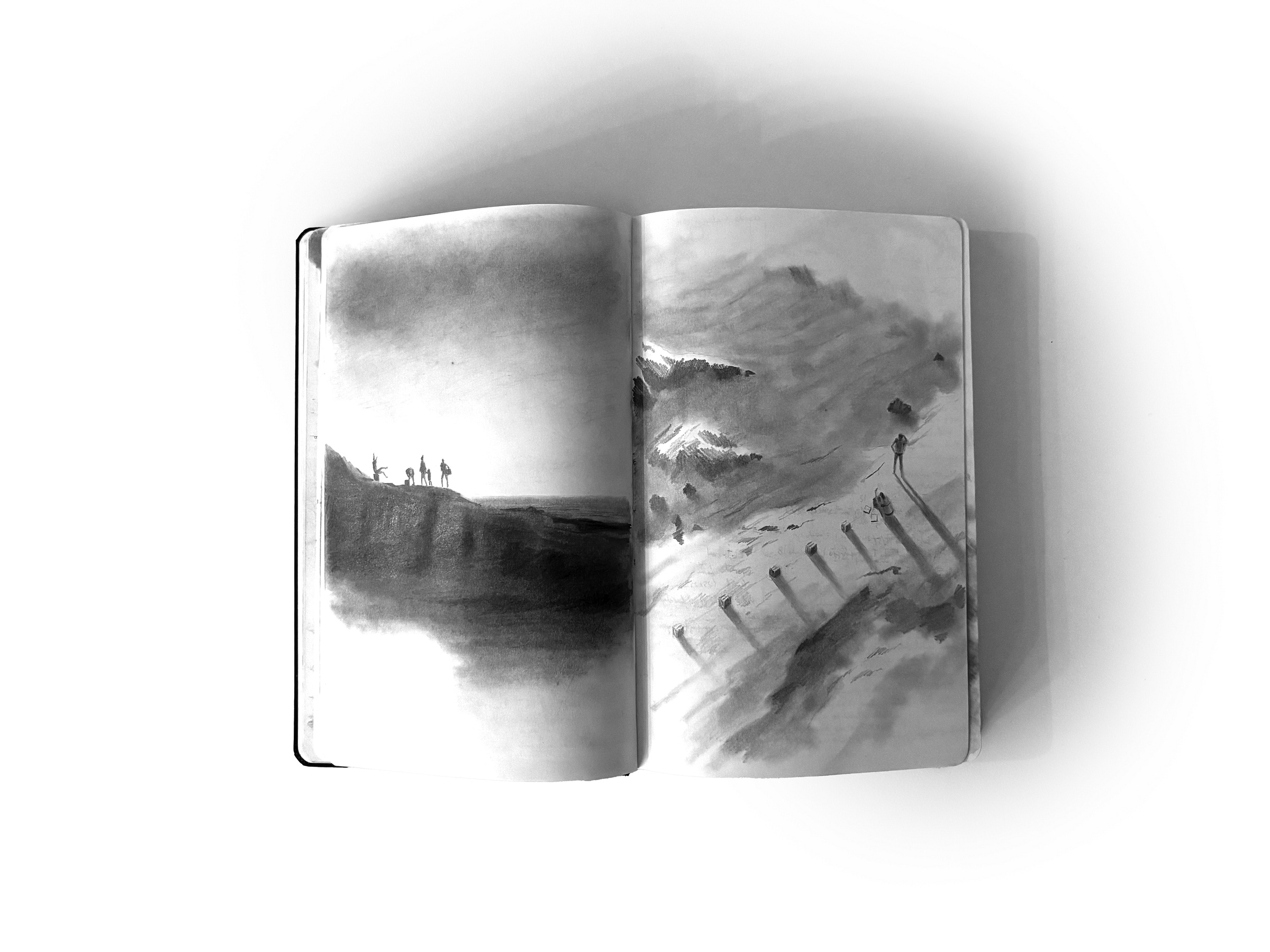

Thus, architecture ceases to be a visual art alone and becomes a corporeal event, understood through touch, movement, smell, and temperature. The building is not an object to be seen, it is an environment to be inhabited. And therefore this embodied experience cannot be diagrammed or modeled; it must be felt, lived, and recalled.

Synthesizing the Non-Quantifiable

At its most basic level, intuition synthesizes non-quantifiable data - atmosphere, memory, emotion - into spatial form. This capacity is profoundly generative. It allows architects to engage not only with function but with feeling and not only with form but with mood. However, this dimension of design is often dismissed as subjective, as though subjective meant illegitimate. In fact, it is precisely this subjectivity that makes architecture matter.

Peter Zumthor exemplifies the sensorial-intuitive paradigm when, in “Thinking Architecture”, he describes how design begins with sensations, instead of programs or theories. In the Therme Vals, he conjures memory - of Alpine geology, of ancient bathing rituals - to create a tactile choreography of stone, water, and light. His process is intuitive, embodied and effective. It unfolds like a memory or a dream recalled through the senses. ⁴

This process can be described as a procedural déjà vu: a subconscious weaving of sensory impressions into a coherent form. Intuition collects fragments, sounds, textures, gestures and binds them into a spatial logic that feels inevitable. It is not a leap of faith but a leap of synthesis, a design logic of a different order. It is architecture as resonance, as alignment, as an extension of the body's memory.

In “Alchemy”, behavioral economist Rory Sutherland makes the case for irrationality as a source of innovation. People, he argues, often make decisions that are not based on what is objectively best but on what feels right. Perceived value is constructed through emotional, atmospheric cues. And architecture operates in a similar register: more than the logic of utility alone, focused on the search for ambiance, narrative, and sensation. ⁵

Beyond Efficiency: Atmosphere and Narrative

Architecture is successful not only when it functions but also when it resonates. Efficiency alone does not create atmosphere; narrative does. The so-called irrational dimension is not a flaw - it is a different intelligence, one capable of orchestrating space as an emotional and cultural performance.

One of intuition’s greatest strengths lies in its contextual intelligence. Rationalism abstracts and generalizes, often leading to designs that ignore specificities of place. Intuition, by contrast, is situated. It responds to nuance, contradiction and particularity. It generates site-specific solutions that no algorithm could predict.

In “The Modern Language of Architecture”, Bruno Zevi criticizes the reduction of architecture to typologies and rules. He praises the work of Frank Lloyd Wright for its intuitive responsiveness - its ability to grow from the terrain, from time, from human need. For Zevi, architecture that feels alive does so because it was conceived beyond abstract ideals, designed through embodied, sensory intelligence.⁶

Christian Norberg-Schulz furthers this perspective by introducing the concept of genius loci: the spirit of place. For him, architecture must make this spirit visible. In his study of vernacular forms, he demonstrates how intuitive responses to climate, light and topography yield buildings that feel both inevitable and unique. These are not generic solutions, they are empathic acts of design. ⁷

This capacity to respond intuitively to context resonates with Aristotle’s notion of phronesis: a practical wisdom rooted in the particular. Just as the ethical person discerns the right action in complex moral situations, the skilled architect senses what a place demands. And this sensitivity cannot be taught through abstract rules - it must be cultivated through practice, attunement and experience. ⁸

Experiencing Architecture as a Whole

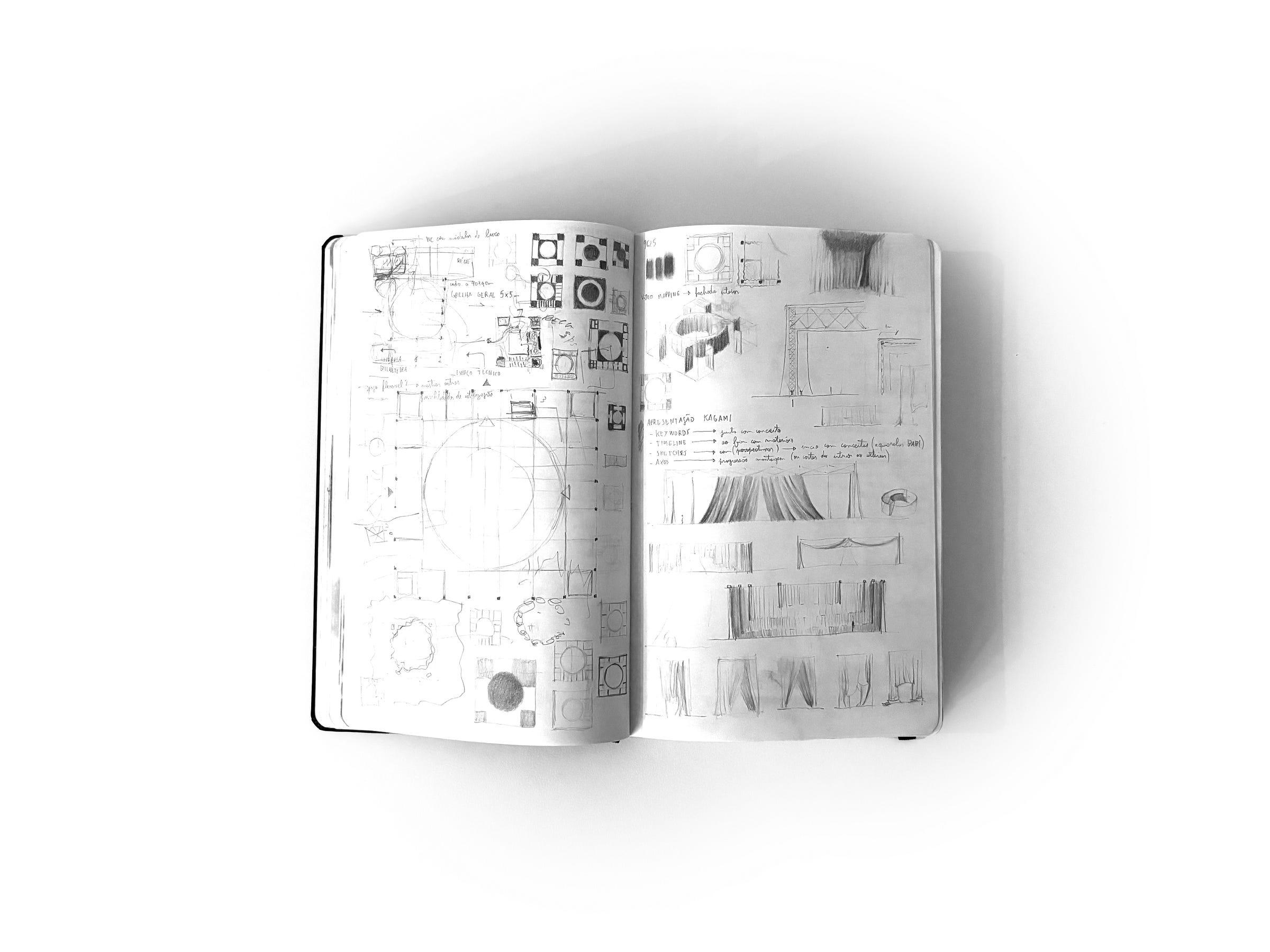

Architecture is never experienced in parts. Nobody perceives walls, roofs or columns individually; human beings experience buildings as immersive wholes. Yet much architectural pedagogy fragments space into categories - function, structure, form - losing the unity of lived experience. Intuition, by contrast, perceives relationships, flows, and moods. It apprehends the whole.

Zumthor’s work showcases this wholeness. In his Serpentine Pavilion, he orchestrated a complete environment: creating a cloistered garden, an ephemeral mood. There was no diagram, only the layering of texture, shadow and sound to induce a contemplative state. The result was spatial poetry.

Similarly, Rory Sutherland’s notion of emotional ecosystems reinforces this view. People do not react to stimuli in isolation; they respond to constellations of sensory inputs. Architecture, like fragrance or music, works on this emotional level. Intuition, with its sensitivity to nuance and tone, is essential to designing such resonance.

Productivity Over Quality

However, in the beginning of the XXI century, as architecture increasingly aligns with economic pressures, it prioritizes productivity over depth. Designs are expected to be fast, efficient and justified, while the richness of intuitive design - its slowness, its ambiguity - is often seen as a liability.

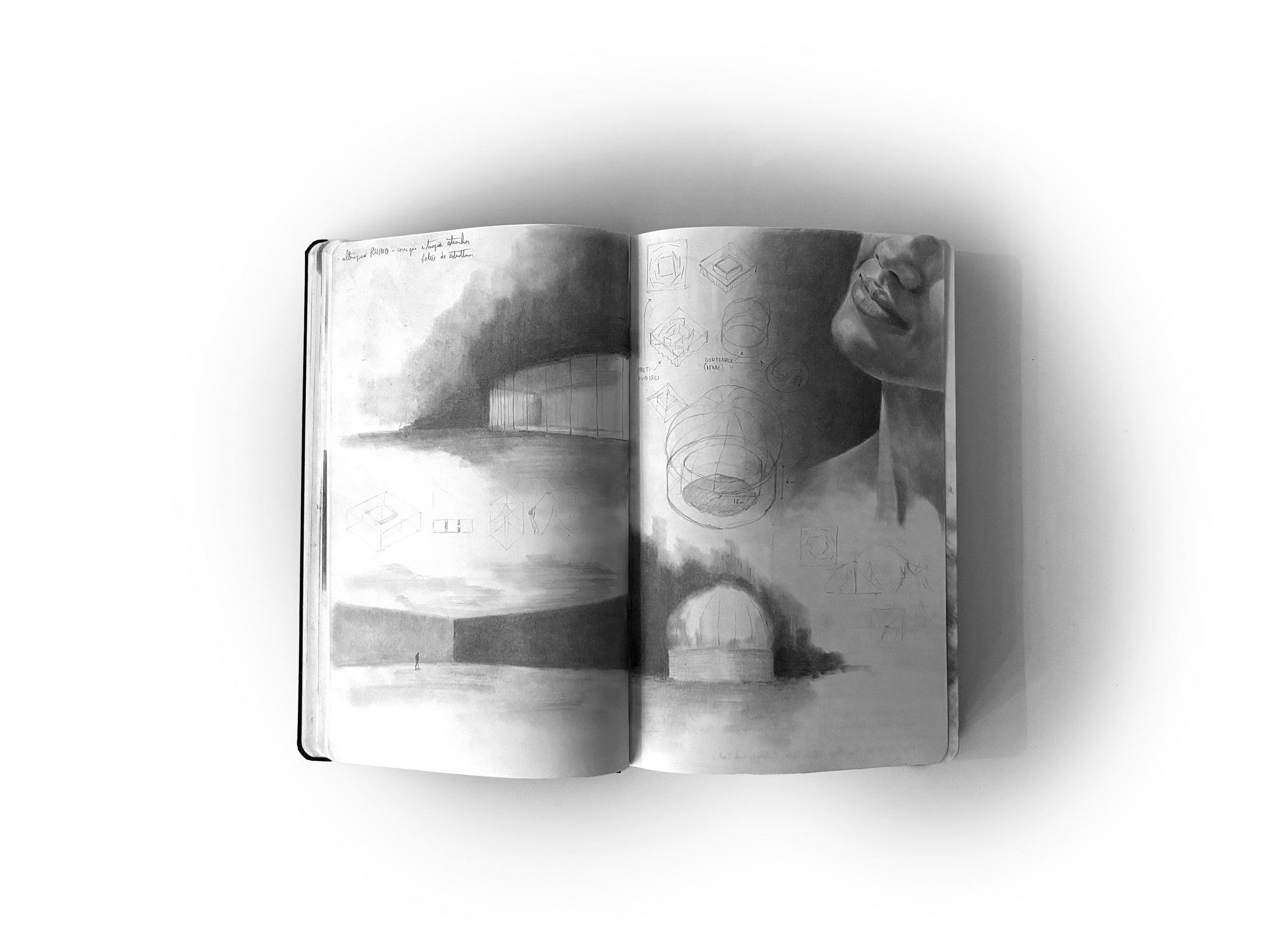

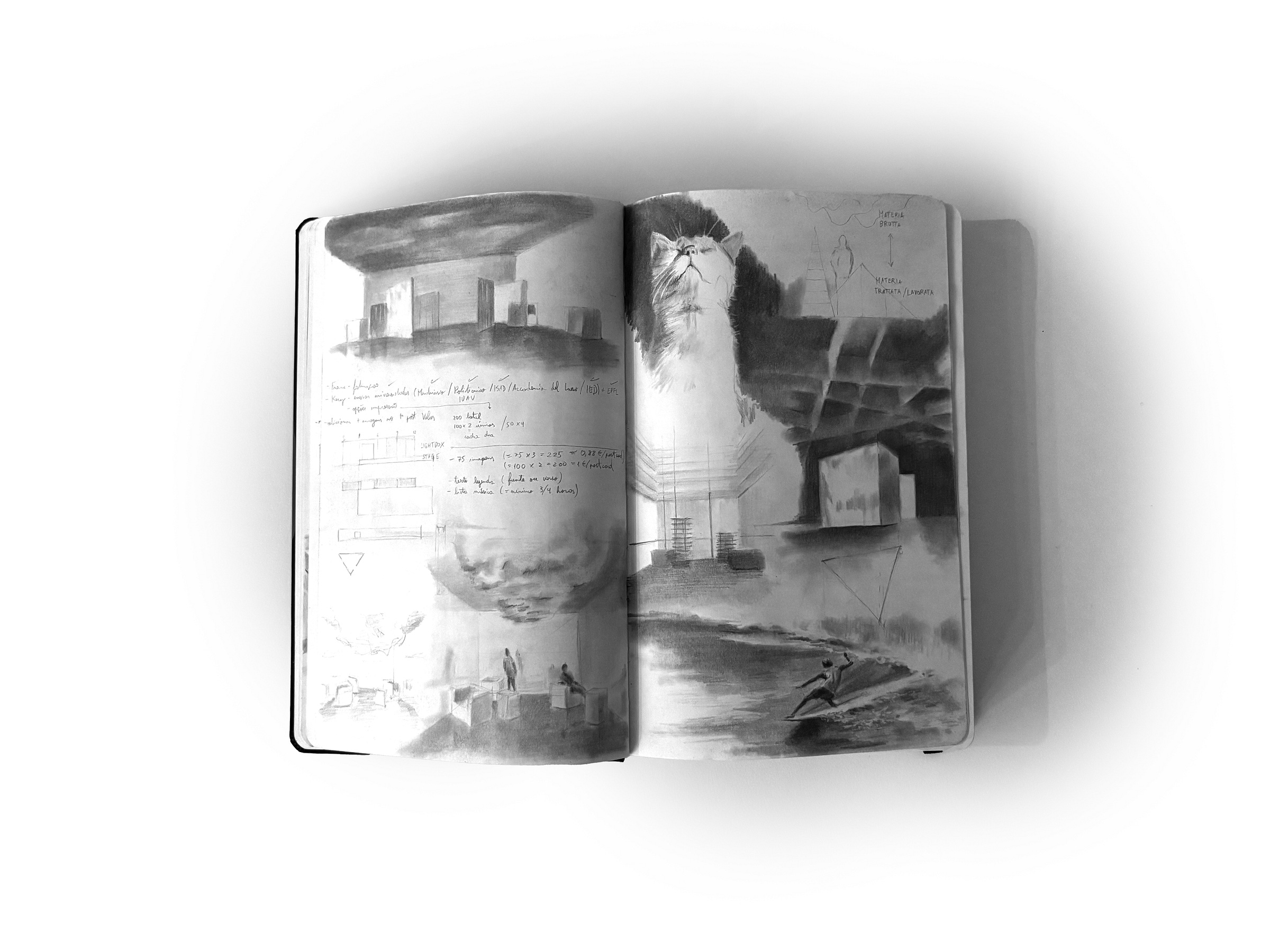

Even pedagogy reflects this bias: students are asked to produce rational diagrams, theoretical frameworks and algorithmic designs. There is little space for intuitive processes, for sketching, daydreaming, or storytelling. These modes of thinking, once central to the discipline, are now marginalized.

Generative tools, while powerful, have contributed to this problem. They produce fast content that often lacks emotional weight or contextual depth. When not guided by intuition, such tools generate formal artifacts detached from place, meaning or memory.

And criticism and theory also further perpetuate this imbalance. The dominant vocabulary privileges rationalization, logic, and causation. There is no equally developed language for describing embodied experience. Until a phenomenological discourse is cultivated, intuition will remain misunderstood - seen as a vague impulse rather than a legitimate form of knowledge.

Intuition as Deeper Intelligence

Yet intuition is not less than reason - it is deeper. It precedes speech, surpasses logic and integrates dimensions that analysis cannot grasp. It brings together the sensory, the emotional and the tacit into a coherent design intelligence. To move beyond rationalism’s narrow confines, It is fundamental to embrace intuition as essential. It is not merely complementary to reason; it is foundational for architectural innovation. It moves the hand, regardless of the mind understanding it. Sketching, model-making, storytelling, and even dreaming are not distractions from design - they are design. These gestures enable people to discover what a context requires, in experiential terms, as their impulses guide the creative act.

In an era where artificial intelligence threatens to render human creativity redundant, intuition may be what truly makes each person - and humanity in general - a fundamental participant in the creation of space.

***

Based in Milan and Paris, EX FIGURA is a collaborative architecture studio that merges art, architecture, design, film and music to generate new realities and combines different skills in a dynamic environment, to always inspire the next project. Founded by Barbara Stallone and Francisco Silva.

References

¹ Plato. The Republic. Translated by G. M. A. Grube and C. D. C. Reeve. Revised edition. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 1992.

² Husserl, Edmund. The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology: An Introduction to Phenomenological Philosophy. Translated by David Carr. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1970.

³ Merleau‑Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by Colin Smith. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1962.

⁴ Zumthor, Peter. Thinking Architecture. 3rd expanded ed. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2010.

⁵ Sutherland, Rory. Alchemy: The Dark Art and Curious Science of Creating Magic in Brands, Business, and Life. New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2019.

⁶ Zevi, Bruno. The Modern Language of Architecture: A Guide to the Anti‑Classical Code. Translated by Anthony Vidler. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1978.

⁷ Norberg‑Schulz, Christian. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture. London: Academy Editions, 1980.

⁸ Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Terence Irwin. 2nd ed. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 1999.